square life (4)

Filed under: daily life, Japan, Kansai, Osaka, photography | Leave a Comment

Tags: Asus ZenFone 3, everyday life, Instagram filter, square, 日常生活, 日常生活の写真

square life (3)

Filed under: daily life, Japan, Kansai, Osaka, photography | Leave a Comment

Tags: Asus ZenFone 3, at war with the obvious, daily life, everyday life, Instagram filter, square, 日常生活, 日常生活の写真

I’m currently in the middle of Typhoon Noru, which has been steadily dropping large amounts of rain over Osaka all day long. It’s a slow-moving typhoon, one that a friend of mine described as “drunken,” so despite the downpour there aren’t any heavy winds to rattle the windows. In fact, in addition to producing some glorious pre-typhoon cloudscapes, it’s provided a bit of break from Osaka’s oppressive summer heat and a good excuse to spend the day indoors.

Despite the unhurried pleasantness of this particular typhoon as I’m experiencing it in Osaka, it has been anything but pleasant for rain-soaked Kyushu, already hit hard this year by record downpours. Similarly, hundreds of thousands had to be evacuated in the Tohoku region during record downpours earlier this year. These downpours are the antipodal counterparts of the record heat waves in Europe and the continuing droughts and forest fires that are devastating California. So, while I’m delighted by the mild demeanor of this typhoon as it passes through Osaka, I can’t also but help to read it in the context of larger trends of global climate destabilization; the atmosphere here is connected to the atmosphere there in a swirl of dynamic causation that is producing climate conditions that in all of human history have never been seen before.

One question that has come up quite a lot recently is the question of how climate destabilization, and the genuine potential of climate catastrophe, should be represented. In her essay A Defense of Climate Tragedy, or What the Scientists Got Wrong about ‘The Uninhabitable Earth,’ Genevieve Guenther* argues that literary representation can play a major role in producing the types of emotional urgency that are the necessary prerequisites for the social and political action that is needed to prevent the worst case scenarios featured in David Wallace-Wells’s essay The Uninhabitable Earth from becoming reality. As Guenther points out in her well-reasoned response to the objections that some climate scientists have to what they see as the dangerous exaggerations of Wallace-Wells’s writing, imaginative writing serves a different – and vitally important – function than science reporting. I agree strongly with Guenther that it is vitally important at this stage to instigate changes in how we understand climate disruption so that this understanding becomes part of our core cultural and emotional awareness of the world, not simply a series of rationally apprehended empirical facts that are then somehow bundled to the side so that we can go about our daily lives as if one of the most significantly important shifts in the natural history of the biosphere isn’t already happening now, all around us.

Timothy Morton has argued in Hyperobjects that global warming is a special kind of conceptual object that is so expansive that it defies our apprehension (Stephen Muecke’s review in the Los Angeles Review of Books gives a good introductory account of Morton’s ideas). It is the very unknowability of global warming as an empirically graspable thing that keeps us from engaging with it with the urgency that is necessary. I think this is partially true, but that this inability to grasp the totality of the hyperobject isn’t an epistemological inevitability, but rather is a product of ways of reading and thinking that have been inherited from a social/economic formation that actively discourages taking into account total systems of relations, including relationships that play out at the level of the ecosystem. As Amitav Ghosh asks, “Where is the fiction about climate change?” As it turns out, the forms of realist fiction that make up the legacy of the contemporary novel don’t necessarily lend themselves to discussions of climate catastrophe, which somehow feel unreal and unconvincing within the limited scope of what is allowed to figure as ‘reality’ in these novels. (Science fiction, on the other hand, offers enormous scope for discussions of climate catastrophe; unfortunately, however, science fiction is all too quickly dismissed as being too ‘unrealistic.’)

But there are plenty of authors who do, in fact, begin to approach the kind of representations of total systems in literature that might give us some hope of being able to grasp the totality of hyperobjects on both the scientific/rational level and on a deeper level of conceptualization as well. Jorie Graham’s incredibly vital, beautiful, and elegiac poems in Sea Change confront what it means to be conscious of the catastrophe befalling the natural world and attempt to open us up to the wonder of creation, even as vanishes before our eyes. As Graham states in an interview with Deidre Wengen,

The overwhelming sensation that rises before me each day. Sometimes I feel I am living an extended farewell, where my eventual disappearance, my mortal nature, normally a deep human concern, has been washed away by my fear for the deeper mortality—the extinction-of other species, and of the natural world itself. I cannot look at the world hard enough.

In “Ezra Pound’s Proposition,” a short poem by Robert Hass published in The American Poetry Review, he shows the immediacy of connections between the World Bank, international finance capital, ecological destruction, and the cultural and social displacement that is a result of the construction of dams. The neon light of prostitution is no longer a de-historicized local phenomenon in this figuration, but instead a visceral and quite literally concrete manifestation of the abstract workings of global finance capital.

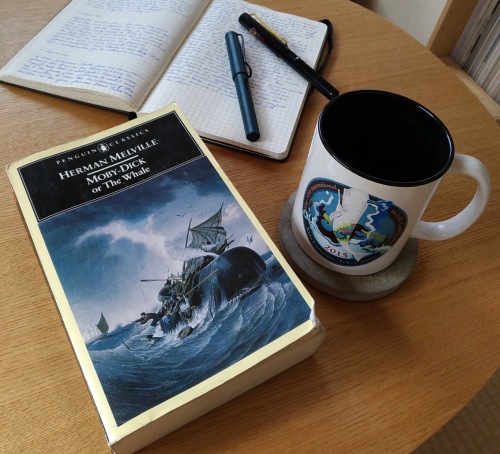

In Moby-Dick, which I’m currently rereading in preparation for a graduate-level summer intensive course that I’ll be teaching, Melville makes a similar move when he ties the brutality inherent in the production of whale oil to the act of reading itself:

Though most men have some vague flitting ideas of the general

perils of the grand fishery, yet they have nothing like a fixed, vivid

conception of those perils, and the frequency with which they recur.

One reason perhaps is, that not one in fifty of the actual disasters

and deaths by casualties in the fishery, ever finds a public record

at home, however transient and immediately forgotten that record.

Do you suppose that that poor fellow there, who this moment perhaps

caught by the whale-line off the coast of New Guinea, is being

carried down to the bottom of the sea by the sounding leviathan–

do you suppose that that poor fellow’s name will appear in the newspaper

obituary you will read to-morrow at your breakfast? No: because the

mails are very irregular between here and New Guinea. In fact,

did you ever hear what might be called regular news direct or indirect

from New Guinea? Yet I will tell you that upon one particular voyage

which I made to the Pacific, among many others we spoke thirty

different ships, every one of which had had a death by a whale,

some of them more than one, and three that had each lost a boat’s crew.

For God’s sake, be economical with your lamps and candles! not a gallon

you burn, but at least one drop of man’s blood was spilled for it.

Melville begins this passage by pointing out to the reader that, in general, knowledge regarding whaling is in short supply, unlike whale oil which was an incredibly common commodity in the 19th century. Whale oil was particular favored for use in reading lamps and for a good portion of the 19th century was very literally the stuff of enlightenment. The knowledge of whaling that is brought to the reader of Moby-Dick doesn’t consist merely of a couple of stories about New Guinea, but rather emerges from the whole of the novel itself, which provides a comprehensive account of the whaling industry down to the last fluke. Once this knowledge has been absorbed by the reader, the reader becomes a self-aware node positioned within a network of industrial production that generates enormous levels of violence in the production of the very spermaceti oil that keeps the lamp fires bright.

What the reader does with this knowledge is a question for another time. But what we do with the knowledge of how we function as nodes within a larger system of industrial consumer production is certainly the question for our times – one that will be being asked, and answered, with an increasing sense of urgency.

*Full disclosure department: I’ve been a friend of Genevieve’s since graduate school and I am totally and completely biased in her favor.

Filed under: books, culture, Japan, Kansai, literature, nature, Osaka, philosophy, poetics, poetry, science, society | 1 Comment

Tags: A Defense of Climate Tragedy, Amitav Ghosh, climate catastrophe, climate fiction, climate science, dam construction, David Wallace-Wells, Deidre Wengen, extreme weather, Ezra Pound's Proposition, Genevieve Guenther, global climate change, global finance capital, hyperobjects, Jorie Graham, literary realism, Melville, Moby-Dick, questions for our times, Robert Hass, Sea Change, The Uninhabitable Earth, Timothy Morton, typhoon, Typhoon Noru, whale oil, whaling

textural (10)

Filed under: daily life, Japan, Kansai, Osaka, photography | Leave a Comment

Tags: Asus ZenFone 3, at war with the obvious, everyday life, vernacular photography, 日常生活, 日常生活の写真

textural (9)

Filed under: daily life, Japan, Kansai, Osaka, photography | Leave a Comment

Tags: Asus ZenFone 3, at war with the obvious, daily life, everyday life, 日常生活, 日常生活の写真

cha

Two of my poems have been included in the special “Writing Japan” issue of Cha: An Asian Literary Journal. The “Writing Japan” issue was edited by Kyoko Yoshida and James Shea, who discuss the process of putting the issue together in this wonderful editorial essay. So many talented writers have work in this issue, including Yoko Danno, Goro Takano, Gregory Dunne, Mariko Nagai, Loren Goodman, Jordan Smith, and many others. I’m over the moon to be included with them.

Filed under: Japan, literature, poetry, sweet story of Trout Monroe, writing | Leave a Comment

Tags: Cha, Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, Goro Takano, Gregory Dunne, James Shea, Jordan Smith, Kyoko Yoshida, Loren Goodman, Mariko Nagai, poetry, Writing Japan, Yoko Danno